Guillain–Barré syndrome

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

| ICD-10 | G61.0 |

| ICD-9 | 357.0 |

| OMIM | 139393 |

| DiseasesDB | 5465 |

| MedlinePlus | 000684 |

| eMedicine | emerg/222 neuro/7 pmr/48 neuro/598 |

| MeSH | D020275 |

Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS) (French pronunciation: [ɡiˈjɛ̃ baˈʁe];[1][2] in English, pronounced /ˈɡiːlæn ˈbɑreɪ/,[3] /ɡiːˈlæn bəˈreɪ/,[4] etc.[5]) is an acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (AIDP), an autoimmune disorder affecting the peripheral nervous system, usually triggered by an acute infectious process. The syndrome was named after the French physicians Guillain, Barré and Strohl, who were the first to describe it in 1916. It is sometimes called Landry's paralysis, after the French physician who first described a variant of it in 1859. It is included in the wider group of peripheral neuropathies. There are several types of GBS, but unless otherwise stated, GBS refers to the most common form, AIDP. GBS is rare and has an incidence of 1 or 2 people per 100,000.[6] It is frequently severe and usually exhibits as an ascending paralysis noted by weakness in the legs that spreads to the upper limbs and the face along with complete loss of deep tendon reflexes. With prompt treatment by plasmapheresis or intravenous immunoglobulins and supportive care, the majority of patients will regain full functional capacity. However, death may occur if severe pulmonary complications and autonomic nervous system problems are present.[7] Guillain-Barré is one of the leading causes of non-trauma-induced paralysis in the world.

.jpg)

Contents |

Classification

Six different subtypes of Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS) exist:

- Acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (AIDP) is the most common form of GBS, and the term is often used synonymously with GBS. It is caused by an auto-immune response directed against Schwann cell membranes.

- Miller Fisher syndrome (MFS) is a rare variant of GBS and manifests as a descending paralysis, proceeding in the reverse order of the more common form of GBS. It usually affects the eye muscles first and presents with the triad of ophthalmoplegia, ataxia, and areflexia. Anti-GQ1b antibodies are present in 90% of cases.

- Acute motor axonal neuropathy (AMAN),[8] aka Chinese Paralytic Syndrome, attacks motor nodes of Ranvier and is prevalent in China and Mexico. It is probably due to an auto-immune response directed against the axoplasm of peripheral nerves. The disease may be seasonal and recovery can be rapid. Anti-GD1a antibodies[9] are present. Anti-GD3 antibodies are found more frequently in AMAN.

- Acute motor sensory axonal neuropathy (AMSAN) is similar to AMAN but also affects sensory nerves with severe axonal damage. Like AMAN, it is probably due to an auto-immune response directed against the axoplasm of peripheral nerves. Recovery is slow and often incomplete.[10]

- Acute panautonomic neuropathy is the most rare variant of GBS, sometimes accompanied by encephalopathy. It is associated with a high mortality rate, owing to cardiovascular involvement, and associated dysrhythmias. Impaired sweating, lack of tear formation, photophobia, dryness of nasal and oral mucosa, itching and peeling of skin, nausea, dysphagia, constipation unrelieved by laxatives or alternating with diarrhea occur frequently in this patient group. Initial nonspecific symptoms of lethargy, fatigue, headache, and decreased initiative are followed by autonomic symptoms including orthostatic lightheadedness, blurring of vision, abdominal pain, diarrhea, dryness of eyes, and disturbed micturition. The most common symptoms at onset are related to orthostatic intolerance, as well as gastrointestinal and sudomotor dysfunction (Suarez et al. 1994). Parasympathetic impairment (abdominal pain, vomiting, obstipation, ileus, urinary retention, dilated unreactive pupils, loss of accommodation) may also be observed.

- Bickerstaff’s brainstem encephalitis (BBE), is a further variant of Guillain–Barré syndrome. It is characterized by acute onset of ophthalmoplegia, ataxia, disturbance of consciousness, hyperreflexia or Babinski’s sign (Bickerstaff, 1957; Al-Din et al.,1982). The course of the disease can be monophasic or remitting-relapsing. Large, irregular hyperintense lesions located mainly in the brainstem, especially in the pons, midbrain and medulla are described in the literature. BBE despite severe initial presentation usually has a good prognosis. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) plays a critical role in the diagnosis of BBE.

A considerable number of BBE patients have associated axonal Guillain–Barré syndrome, indicative that the two disorders are closely related and form a continuous spectrum.

Signs and symptoms

The disorder is characterized by symmetrical weakness which usually affects the lower limbs first, and rapidly progresses in an ascending fashion. Patients generally notice weakness in their legs, manifesting as "rubbery legs" or legs that tend to buckle, with or without dysesthesias (numbness or tingling). As the weakness progresses upward, usually over periods of hours to days, the arms and facial muscles also become affected. Frequently, the lower cranial nerves may be affected, leading to bulbar weakness, oropharyngeal dysphagia (drooling, or difficulty swallowing and/or maintaining an open airway) and respiratory difficulties. Most patients require hospitalization and about 30% require ventilatory assistance.[11] Facial weakness is also commonly a feature, but eye movement abnormalities are not commonly seen in ascending GBS, but are a prominent feature in the Miller-Fisher variant (see below.) Sensory loss, if present, usually takes the form of loss of proprioception (position sense) and areflexia (complete loss of deep tendon reflexes), an important feature of GBS. Loss of pain and temperature sensation is usually mild. In fact, pain is a common symptom in GBS, presenting as deep aching pain, usually in the weakened muscles, which patients compare to the pain from overexercising. These pains are self-limited and should be treated with standard analgesics. Bladder dysfunction may occur in severe cases but should be transient. If severe, spinal cord disorder should be suspected.

Fever should not be present, and if it is, another cause should be suspected.

In severe cases of GBS, loss of autonomic function is common, manifesting as wide fluctuations in blood pressure, orthostatic hypotension, and cardiac arrhythmias.

Acute paralysis in Guillain–Barré syndrome may be related to sodium channel blocking factor in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Significant issues involving intravenous salt and water administration may occur unpredictably in this patient group, resulting in SIADH. SIADH is one of the causes of hyponatremia and can be accompanied with various conditions such as malignancies, infections and nervous system diseases. Symptoms of Guillain- Barre syndrome such as general weakness, decreased consciousness, and seizure are similar to those of hyponatremia

The symptoms of Guillain–Barré syndrome are also similar to those for progressive inflammatory neuropathy.[12]

Cause

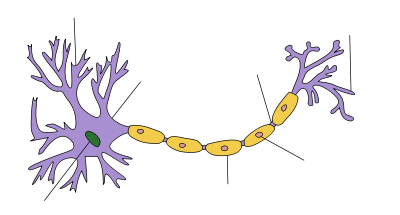

| Neuron |

|---|

All forms of Guillain–Barré syndrome are due to an immune response to foreign antigens (such as infectious agents) that are mistargeted at host nerve tissues instead. The targets of such immune attack are thought to be gangliosides, compounds naturally present in large quantities in human nerve tissues. The most common antecedent infection is the bacterium Campylobacter jejuni.[13][14] However, 60% of cases do not have a known cause; one study suggests that some cases are triggered by the influenza virus, or by an immune reaction to the influenza virus.[15]

The end result of such autoimmune attack on the peripheral nerves is damage to the myelin, the fatty insulating layer of the nerve, and a nerve conduction block, leading to a muscle paralysis that may be accompanied by sensory or autonomic disturbances.

However, in mild cases, nerve axon (the long slender conducting portion of a nerve) function remains intact and recovery can be rapid if remyelination occurs. In severe cases, axonal damage occurs, and recovery depends on the regeneration of this important tissue. Recent studies on the disorder have demonstrated that approximately 80% of the patients have myelin loss, whereas, in the remaining 20%, the pathologic hallmark of the disorder is indeed axon loss.

Guillain-Barré, unlike disorders such as multiple sclerosis (MS) and Lou Gehrig's disease (ALS), is a peripheral nerve disorder and does not generally cause nerve damage to the brain or spinal cord.

Influenza vaccine

GBS may be a rare side-effect of influenza vaccines; a study of the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) indicates that it is reported as an adverse event potentially associated with the vaccine at a rate of an excess of 1 per million vaccines (over the normal risk).[16] There were reports of GBS affecting an excess of 10 per million who had received swine flu immunizations in the 1976 U.S. outbreak of swine flu—25 of which resulted in death from severe pulmonary complications, leading the government to end that immunization campaign.[17] However, the role of the vaccine in these cases has remained unclear, partly because GBS had an unknown but very low incidence rate in the general population making it difficult to assess whether the vaccine was really increasing the risk for GBS. Later research has pointed to the absence of or only a very small increase in the GBS risk due to the 1976 swine flu vaccine.[18] Furthermore, the GBS may not have been directly due to the vaccine but to a bacterial contamination of the vaccine.[19]

Since 1976, no other influenza vaccines have been linked to GBS, though as a precautionary principle, caution is advised for certain individuals, particularly those with a history of GBS.[20][21] On the other hand, getting infected by the flu increases the risk of developing GBS to a much higher level (approx. 10 times higher by recent estimates[22]).R, Sharshar T, Durand MC, Enouf V, et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome and influenza virus infection. Clin Infect Dis 2009;48:48-56.</ref>

From October 6 to November 24, 2009, the U.S. CDC, through the VAERS reporting system, received ten reports of Guillain-Barre syndrome cases associated with the H1N1 vaccine and identified two additional probable cases from VAERS reports (46.2 million doses were distributed within the U.S. during this time). Only four cases, however, meet the Brighton Collaboration Criteria for Guillain–Barré syndrome, while four do not meet the criteria and four remain under review.[23] A preliminary report by the CDC's Emerging Infections Programs (EIP) calculates the rate of GBS observed in patients who previously received the 2009 H1N1 influenza vaccination is an excess of 0.8 per million cases, which is on par with the rate seen with the seasonal trivalent influenze vaccine. [24]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of GBS usually depends on findings such as rapid development of muscle paralysis, areflexia, absence of fever, and a likely inciting event. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis (through a lumbar spinal puncture) and electrodiagnostic tests of nerves and muscles (such as nerve conduction studies) are common tests ordered in the diagnosis of GBS.

- Typical CSF findings include albumino-cytological dissociation. As opposed to infectious causes, this is an elevated protein level (100–1000 mg/dL), without an accompanying increased cell count pleocytosis. A sustained increased white blood cell count may indicate an alternative diagnosis such as infection.

- Electrodiagnostics

- Electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction study (NCS) may show prolonged distal latencies, conduction slowing, conduction block, and temporal dispersion of compound action potential in demyelinating cases. In primary axonal damage, the findings include reduced amplitude of the action potentials without conduction slowing.

Diagnostic criteria

Required

- Progressive, relatively symmetrical weakness of two or more limbs due to neuropathy

- Areflexia

- Disorder course < 4 weeks

- Exclusion of other causes (see below)

Supportive

- relatively symmetric weakness accompanied by numbness and/or tingling

- mild sensory involvement

- facial nerve or other cranial nerve involvement

- absence of fever

- typical CSF findings obtained from lumbar puncture

- electrophysiologic evidence of demyelination from electromyogram

Differential diagnosis

- acute myelopathies with chronic back pain and sphincter dysfunction

- botulism with early loss of pupillary reactivity and descending paralysis

- diphtheria with early oropharyngeal dysfunction

- Lyme disease polyradiculitis and other tick-borne paralyses

- porphyria with abdominal pain, seizures, psychosis

- vasculitis neuropathy

- poliomyelitis with fever and meningeal signs

- CMV polyradiculitis in immunocompromised patients

- critical illness neuropathy

- myasthenia gravis

- poisonings with organophosphate, poison hemlock, thallium, or arsenic

- paresis caused by West Nile virus

- spinal astrocytoma

- Motor Neurone Disease

- West Nile virus can cause severe, potentially fatal neurological illnesses, which include encephalitis, meningitis, Guillain-Barre syndrome, and anterior myelitis.

- Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome.

Management

Supportive care with monitoring of all vital functions is the cornerstone of successful management in the acute patient. Of greatest concern is respiratory failure due to paralysis of the diaphragm. Early intubation should be considered in any patient with a vital capacity (VC) <20 ml/kg, a negative inspiratory force (NIF) <-25 cmH2O, more than 30% decrease in either VC or NIF within 24 hours, rapid progression of disorder, or autonomic instability.

Once the patient is stabilized, treatment of the underlying condition should be initiated as soon as possible. Either high-dose intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIg) at 400 mg/kg for 5 days or plasmapheresis can be administered,[25][26] as they are equally effective and a combination of the two is not significantly better than either alone. Therapy is no longer effective two weeks after the first motor symptoms appear, so treatment should be instituted as soon as possible. IVIg is usually used first because of its ease of administration and safety profile, with a total of five daily infusions for a total dose of 2 g/kg body weight (400 mg/kg each day). The use of intravenous immunoglobulins is not without risk, occasionally causing hepatitis, or in rare cases, renal failure if used for longer than five days. Glucocorticoids have not been found to be effective in GBS. If plasmapheresis is chosen, a dose of 40-50 mL/kg plasma exchange (PE) can be administered four times over a week.

Following the acute phase, the patient may also need rehabilitation to regain lost functions. This treatment will focus on improving ADL (activities of daily living) functions such as brushing teeth, washing, and getting dressed. Depending on the local structuring on health care, a team of different therapists and nurses will be established according to patient needs. An occupational therapist can offer equipment (such as wheelchair and special cutlery) to help the patient achieve ADL independence. A physiotherapist would plan a progressive training program and guide the patient to correct, functional movement, avoiding harmful compensations which might have a negative effect in the long run. A speech and language therapist would be essential in the patient regaining speaking and swallowing ability if they were intubated and received a tracheostomy. The speech and language therapist would also offer advice to the medical team regarding the swallowing abilities of the patient and would help the patient regain their communication ability pre-dysarthria. There would also be a doctor, nurse and other team members involved, depending on the needs of the patient. This team contribute their knowledge to guide the patient towards his or her goals, and it is important that all goals set by the separate team members are relevant for the patient's own priorities. After rehabilitation the patient should be able to function in his or her own home and attend necessary training as needed.

Prognosis

Most of the time recovery starts after the fourth week from the onset of the disorder. Approximately 80% of patients have a complete recovery within a few months to a year, although minor findings may persist, such as areflexia. About 5–10% recover with severe disability, with most of such cases involving severe proximal motor and sensory axonal damage with inability of axonal regeneration. However, this is a grave disorder and despite all improvements in treatment and supportive care, the death rate among patients with this disorder is still about 2–3% even in the best intensive care units. Worldwide, the death rate runs slightly higher (4%), mostly from a lack of availability of life support equipment during the lengthy plateau lasting four to six weeks, and in some cases up to one year, when a ventilator is needed in the worst cases. About 5–10% of patients have one or more late relapses, in which case they are then classified as having chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP).

Poor prognostic factors include: 1) age >40 years, 2) history of preceding diarrheal illness, 3) requiring ventilator support, 4) high anti-GM1 titre and 5) poor upper limb muscle strength.

Case reports do exist of rapid patient recovery.

Epidemiology

The incidence of GBS during pregnancy is 1.7 cases per 100,000 of the population.[27] The mother will generally improve with treatment but death of the fetus is a risk. The risk of Guillain–Barré syndrome increases after delivery, particularly during the first two weeks postpartum. There is evidence of Campylobacter jejuni as an antecedent infection in approximately 26% of disease cases, requiring special care in the preparation and handling of food. Congenital and neonatal Guillain–Barré syndrome have also been reported.[28]

History

The disorder was first described by the French physician Jean Landry in 1859. In 1916, Georges Guillain, Jean Alexandre Barré, and André Strohl diagnosed two soldiers with the illness and discovered the key diagnostic abnormality of increased spinal fluid protein production, but normal cell count.[29]

GBS is also known as acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy, acute idiopathic polyradiculoneuritis, acute idiopathic polyneuritis, French Polio, Landry's ascending paralysis and Landry Guillain Barré syndrome.

Notable cases

- Andy Griffith, American actor on Andy Griffith Show, and Matlock. He developed Guillain–Barré in 1983.[30]

- Rachel Chagall, actress, contracted GBS in 1982. In 1987 she portrayed Gabriela Brimmer, a notable disabilities activist.[31]

- Joseph Heller, author, contracted GBS in 1981. This episode in his life is recounted in the autobiographical No Laughing Matter, which contains alternating chapters by Heller and his good friend Speed Vogel.[32]

- Franklin D. Roosevelt, U.S. president. In 2003, a peer-reviewed study[33] found that it was more likely that Roosevelt's paralysis—long attributed to poliomyelitis—was actually Guillain–Barré syndrome.

- Diomedes Diaz, A Colombian vallenato artist.

- Markus Babbel, former international footballer, contracted GBS in 2001, following a period suffering from the Epstein–Barr virus. He lost almost an entire year of his footballing career between the two illnesses and never again demonstrated the same level of ability that won him over 50 caps for Germany.[34]

- Serge Payer, Canadian-born professional hockey player. After battling and overcoming the syndrome, he set up the Serge Payer Foundation, which is dedicated to raising money for research into new treatments and cures for Guillain–Barré syndrome.[35]

- Hans Vonk, Dutch conductor.[36]

- Lucky Oceans, Grammy Award winning musician with Asleep at the Wheel was diagnosed with GBS in 2008.[37]

- William “The Refrigerator” Perry, former professional American football player with the Chicago Bears was diagnosed with GBS in 2008.[38]

- Tony Benn, British politician.[39]

- Len Pasquarelli, sports writer and analyst for ESPN and resident of the Pro Football Writers of America, diagnosed in 2008.[40]

- Hiroko Mima, Miss Universe Japan 2008, was diagnosed with GBS at the age of 13.[41]

- Norton Simon[42]

- Hugh McElhenny, former Hall-of-Fame, professional American football player with the San Francisco 49ers.[43]

- Luci Baines Johnson, daughter of President Lyndon Johnson and Lady Bird Johnson. Diagnosed and under treatment for Guillain–Barré in April 2010.[44]

- Zeituni Onyango, paternal aunt of U.S. President Barack Obama.[45]

- Scott Klopfenstein, member of American ska-punk band Reel Big Fish. In September 2005, Klopfenstein was diagnosed with GBS while touring New Zealand.

References

- ↑ "John Wells's phonetic blog, 23 February 2007". http://www.phon.ucl.ac.uk/home/wells/blog0702b.htm.

- ↑ "See also, in the same blog, the entry of 20 October 20, 2008". http://www.phon.ucl.ac.uk/home/wells/blog0811.htm.

- ↑ Recommended by the "GBS Support Group". http://www.gbs.org.uk/quickguide.html.

- ↑ "Guillain–Barré Syndrome". Dictionary.com Unabridged (v 1.1). Random House. http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/Guillain-Barre%20Syndrome.

- ↑ In English, Guillain may be pronounced with an L sound as in French, but it is common to pronounce it without one, originally based on the mistaken assumption that the French pronunciation of the ll is [j] and not [l]. In English, both Guillain and Barré may be pronounced with the stress on either the first or the last syllable. The nasal vowel [ɛ̃] at the end of Guillain is either kept in English or replaced by a sequence of an oral vowel and a nasal consonant such as [æn].

- ↑ Mayo Clinic.com. GBS definition.. Retrieved 8-20-2009.

- ↑ U.S. National Library of Medicine. Medline Plus: "Guillain–Barré syndrome". Retrieved 8-28-2009.

- ↑ McKhann GM, Cornblath DR, Ho T, et al (1991). "Clinical and electrophysiological aspects of acute paralytic disease of children and young adults in northern China". Lancet 338 (8767): 593–7. doi:10.1016/0140-6736(91)90606-P. PMID 1679153.

- ↑ Ho TW, Mishu B, Li CY, et al (1995). "Guillain-Barré syndrome in northern China. Relationship to Campylobacter jejuni infection and anti-glycolipid antibodies". Brain 118 ( Pt 3): 597–605. doi:10.1093/brain/118.3.597. PMID 7600081. http://brain.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=7600081.

- ↑ Griffin JW, Li CY, Ho TW, et al (1995). "Guillain–Barré syndrome in northern China. The spectrum of neuropathological changes in clinically defined cases". Brain 118 ( Pt 3): 577–95. doi:10.1093/brain/118.3.577. PMID 7600080. http://brain.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=7600080.

- ↑ EMedicine from WebMD, Guillain-Barré.. Retrieved 8-20-2009.

- ↑ David Brown (2008-02-04). "Inhaling Pig Brains May Be Cause of New Illness". The Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2008/02/03/AR2008020302580.html?hpid=topnews. Retrieved 2008-02-04.

- ↑ Yuki N (June 2008). "[Campylobacter genes responsible for the development and determinant of clinical features of Guillain-Barré syndrome]" (in Japanese). Nippon Rinsho. Japanese Journal of Clinical Medicine 66 (6): 1205–10. PMID 18540372.

- ↑ Kuwabara S. et al. (2004-08-10). "Does Campylobacter jejuni infection elicit "demyelinating" Guillain-Barré syndrome?". Neurology (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins) 63 (3): 529–33. PMID 15304587.

- ↑ Sivadon-Tardy V. et al. (Jan. 1 2009). "Guillain-Barré syndrome and influenza virus infection". Clinical Infectious Diseases (The University of Chicago Press) 48 (1): 48–56. PMID 19025491.

- ↑ PMID 19356614 (PubMed)

Citation will be completed automatically in a few minutes. Jump the queue or expand by hand - ↑ Silverstein A. Pure politics and impure science. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 1981.

- ↑ “Prepandemic” Immunization for Novel Influenza Viruses, “Swine Flu” Vaccine, Guillain‐Barré Syndrome, and the Detection of Rare Severe Adverse Events. David Evans, Simon Cauchemez, Frederick G Hayden. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 2009;200:321–328

- ↑ Paul Harasim (March 25, 2009). "Flu Shots: Vaccine decisions complex – But Nevada's health officer has no doubts what to do". Las Vegas Review-Journal. http://www.lvrj.com/news/45975417.html. "The 1978 book The Swine Flu Affair revealed that the risk of developing Guillain–Barré syndrome was about eleven times greater with the vaccination than without. Yet it noted that the risk was very low; about one in 105,000 who were vaccinated got it."

- ↑ Haber P, Sejvar J, Mikaeloff Y, Destefano F (2009). "Vaccines and Guillain-Barré Syndrome". Drug Saf 32 (4): 309–23.. doi:10.2165/00002018-200932040-00005 (inactive 2009-04-26). PMID 19388722.

- ↑ "Influenza / Flu Vaccine". University of Illinois at Springfield. http://www.uis.edu/healthservices/immunizations/influenzavaccine.html. Retrieved 26 April 2009.

- ↑ Stowe J, Andrews N, Wise L, Miller E. Investigation of the temporal association of Guillain-Barré syndrome with influenza vaccine and influenza-like illness using the United Kingdom General Practice Research Database. Am J Epidemiol 2009;169:382-8.

- ↑ "Safety of Influenza A (H1N1) 2009 Monovalent Vaccines --- United States, October 1--November 24, 2009". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm58e1204a1.htm?s_cid=mm58e1204a1_x. Retrieved 5 December 2009.

- ↑ "Preliminary Results: Surveillance for Guillain-Barré Syndrome After Receipt of Influenza A (H1N1) 2009 Monovalent Vaccine --- United States, 2009--2010". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm59e0602a1.htm?s_cid=mm59e0602a1_e%0d%0a. Retrieved 2 June 2010.

- ↑ Merck Manual [Online]. Peripheral Neuropathy, Treatment (no dose info from this ref, though.). Retrieved 8-22-2009.

- ↑ Meythaler, R.G. Miller, J.T. Sladky and J.C. Stevens, R.A.C. Hughes, E.F.M. Wijdicks, R. Barohn, E. Benson, D.R. Cornblath, A. F. Hahn, J.M., "Practice parameter: Immunotherapy for Guillain–Barré syndrome: Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology", Neurology 2003;61;736-740. Download from http://www.neurology.org/cgi/reprint/61/6/736.pdf.

- ↑ Brooks, H; Christian AS; May AE (2000). "Pregnancy, anaesthesia and Guillain-Barré syndrome". Anaesthesia 55 (9): 894–8. PMID 10947755.

- ↑ Iannello, S (2004). Guillain–Barré syndrome: Pathological, clinical and therapeutical aspects. Nova Publishers. ISBN 1594541701. http://books.google.com/books?id=uvwX_ZGJlFoC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_navlinks_s#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- ↑ Guillain-Barré-Strohl syndrome and Miller Fisher's syndrome at Who Named It?

- ↑ "Andy in Guideposts Magazine". http://www.mayberry.com/tagsrwc/wbmutbb/anewsome/private/guidpost.htm.

- ↑ "Gaby, A True Story (1987)". Films involving Disabilities. http://www.disabilityfilms.co.uk/general1/gabyatruestory.htm.

- ↑ Vogel, Speed; Heller, Joseph (2004). No Laughing Matter. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-4717-5.

- ↑ Goldman AS, Schmalstieg EJ, Freeman DH, Goldman DA, Schmalstieg FC (2003). "What was the cause of Franklin Delano Roosevelt's paralytic illness?" (PDF). J Med Biogr 11 (4): 232–40. PMID 14562158. Archived from the original on 2008-03-07. http://web.archive.org/web/20080307005449/http://www.rsmpress.co.uk/jmb_2003_v11_p232-240.pdf.

- ↑ Wallace, Sam (2002-08-10). "Grateful Babbel a tower of strength again". London: Telegraph. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/sport/main.jhtml?xml=/sport/2002/08/10/sfnliv10.xml. Retrieved 2009-11-23.

- ↑ Serge Payer Foundation, Serge Payer Foundation Mission.

- ↑ Kozinn, Allan (2004-08-31). "Hans Vonk, 63, Conductor Of the St. Louis Symphony". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2004/08/31/arts/hans-vonk-63-conductor-of-the-st-louis-symphony.html. Retrieved 2009-08-26.

- ↑ "Lucky Oceans in hospital". The Australian. 2008-10-13. http://www.theaustralian.news.com.au/story/0,,24485771-22822,00.html. Retrieved 2008-10-28.

- ↑ . YumaSun.com. 2008-09-08. http://www.yumasun.com/sports/tatum_44249___article.html/perry_night.html. Retrieved 2008-10-28.

- ↑ "Relative Values: Tony and Josh Benn". London: The Times. 2002-10-17. http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/life_and_style/article824739.ece. Retrieved 2009-01-15.

- ↑ "Chris Mortensen on Len Pasquarelli's comeback". ESPN.com. 2009-01-26. http://sports.espn.go.com/nfl/playoffs2008/columns/story?id=3861360. Retrieved 2009-01-26.

- ↑ "ギラン・バレー症候群". http://mimahiroko.com/?p=379. Retrieved 2009-11-17.

- ↑ "Norton Simon Biography". http://www.nortonsimon.org/about/biography.aspx. Retrieved 13 October 2009.

- ↑ "The untold story of Hugh McElhenny, the King of Montlake". Seattle PI. 2004-09-02. http://www.seattlepi.com/huskies/189001_hugh02.html. Retrieved 2010-01-07.

- ↑ "Luci Baines Johnson hospitalized with nervous system disorder". http://www.austin360.com/blogs/content/shared-gen/blogs/austin/outandabout/entries/2010/04/17/luci_baines_joh.html.

- ↑ http://www.boston.com/news/local/breaking_news/2010/05/obamas_aunt_giv.html

External links

- Mayo Clinic (2009). MayoClinic.com, Guillain-Barré

- GBS/CIDP Foundation International

- Guillain–Barré Syndrome Support Group (UK and Ireland)

- Information from GBS Association of New South Wales (AU)

- NINDS Miller Fisher Syndrome Information Page

- Lucky Oceans interview—Oceans is interviewed by Dr Norman Swan on ABC Radio National (8 March 2009)

- http://www.allingporterfield.com They sell a wonderful book which tells the story of one family's experience with and victory over a severe case of this illness suffered by the husband

- Coming to Grips with Guillain-Barre Syndrome True account of a doctor who panicked when treating a rare disease, and the patient who forged a partnership with him (from The Medical Post 1993, 29(5):32)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||